Postgraduate taught (PGT) programmes offer students opportunities to develop specialised knowledge and skills required for academic practice and professional fields. PGT students constitute 60% of the postgraduate population at the University of Edinburgh. In order to understand PGT student learning and teaching experience so as to improve the quality of the degree programmes, the University of Edinburgh administers a sector-wide survey–the Postgraduate Taught Experience Survey (PTES)–each year during March and June. The survey is owned and managed by The Advance HE consultancy, and highlights key areas of student experience including 1) teaching and learning, 2) engagement, 3) assessment and feedback, 4) dissertation or major project, 5) organisation and management, 6) resources and services, 7) skills development, 8) academic community, 9) personal tutor, 10) career development, and 11) overall satisfaction. Benchmarking dashboards and tables are usually provided by the Advance HE within 6 weeks of the close of the survey to maximise opportunities for action planning based on the results (see the 2019 PTES report).

Although the % agreement of the Edinburgh PGT students to each of the 11 primary themes of the survey is published along with the free-text comments, there has not been any report on the analysis of the text feedback. With access to the data collected between 2017 and 2019, I analysed the responses (3,951 comments) to this particular question–please comment on one thing that would most improve your experience of your course. This Christmas holiday project is my first experience using R to run topic modelling and it has been fun, thanks to Farren Tang’s tutorial.

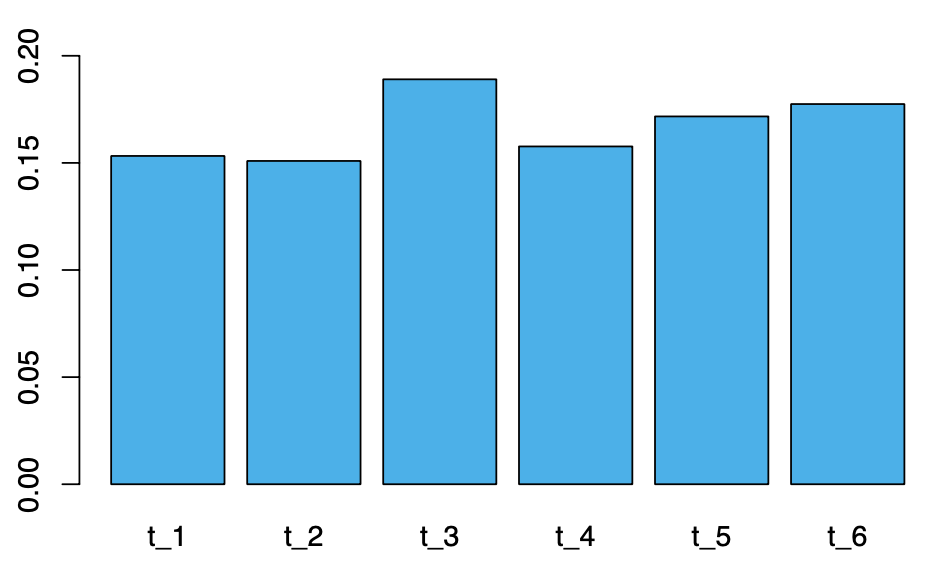

The algorithm grouped the words into six topics, which appeared to correspond to the following areas:

1. Programme context

2. Course structure

3. Feedback and assessment

4. Assignment and skills

5. Learning challenges

6. Learning activities

Below is a table of the top 20 words most likely to be associated with each of the topics identified based on the words in the comments.

After plotting the likelihood of seeing each topic in student responses, we can see that Topic 3 ‘feedback and assessment’ appears to have the highest probability of being mentioned by students when it comes to areas to improve the course experience.

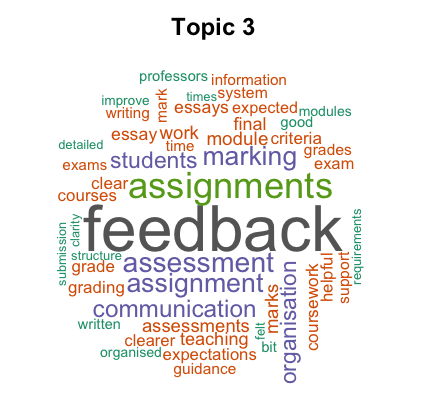

Let’s have a look at the word cloud for this topic (try spot the top 20 words):

The word cloud shows that this topic is best described by words such as feedback, assignment(s), assessment, marking, communication, organisation and students. To put the findings in context, I examined the top 5 responses with the highest probability scores of including Topic 3:

Definitely the marking process. I felt that it was a bit unorganized, subjective, and not always fair. There were times where I received a very high grade on a paper I considered average and very low on other[s] where I felt it deserved better. The process to counteract and change the grade also seems daunting and drawn-out. Some instructors were wonderful and detailed with their feedback, while others provided very little.–Response 1, p(t 3)= 99.1%

Feedback on essays and exams could be more comprehensive although I do understand there are certain constraints to this. Also, I’m not sure if it would be better to have more senior staff marking essays rather than PhD students–the feedback on essays marked by PhD students has not been to the same standard as hat [sic] marked by lecturers.–Response 2, p(t 3)= 98.8%

Clear communication on how essays are assessed, useful feedback on how to improve (rather than being told 65 is a good grade – I’m here to improve not to remain the same), consistency in marking (I’ve received a 55 and a 75 for work I consider the same standard and have not been enlightened as to why).–Response 3, p(t 3)= 98.5%

Occasional inconsistent feedback with marking at times with regards [sic] writing style–this is con- fusing at times.–Response 4, p(t 3)= 98.3%

Marking was inconsistent across different instructors and it often took way to[o] long to get marks back. This normally wouldn’t be a problem, but it prevented me from correcting any habitual mistakes I was making in time for subsequent assignments.–Response 5, p(t 3)= 98.3%

These quotes highlight a number of issues that concerned the students about feedback and assessment practice. Firstly, there is a lack of consistency in both marking and feedback practice. It appears that the issue not only exists in the differences between the practice of different instructors and examiners, but also the gap between students’ own assessment of their work quality and the one carried out by the instructor/ examiner. Secondly, the usefulness of feedback was judged based on how detailed, comprehensive, and timely the feedback is.

Now of course the five comments cannot generalise all the issues raised in the 3,951 comments and a more thorough investigation is needed, but we can see a few common areas highlighted here that deserve our attention. So how may we tackle these areas?

Recommendation 1: Effective feedback needs to address both affective and cognitive dimensions

Learners engage with feedback at three levels: affective (e.g., seeking assurance, developing trust, and cultivating confidence), cognitive (e.g., comprehending feedback and selecting actionable information), and be- havioural (e.g., following or ignoring advice, adjusting learning strategy, and seeking support). The behavioural engagement (i.e., the extent to which students act on feedback) is a function of the affective and cognitive engagement combined. The affective dimension of feedback may contain positive messages that are intended to encourages and motivate students. It is believed that affective engagement with feedback contributes to positive motivation, self-esteem, and a continuous dialogue (Dunworth & Sanchez, 2016; Nicol & Macfarlane- Dick, 2006). On the other hand, the cognitive dimension of feedback needs ‘orientational’ elements (Dunworth & Sanchez, 2016); that is, pointing students to the desired goals and course expectations, and providing them with a sense of their performance in comparison to the course standards and the performance of the peers. The cognitive dimension of feedback also needs to cultivate a capacity for reflection and a sense of autonomy (Dunworth & Sanchez, 2016), i.e., self-regulated capacity (Butler & Winne, 1995).

Recommendation 2: Feedback needs to be planned into formal and peer assessment

It is important to incorporate feedback guidelines into the instructions for examiners so as to raise the awareness of their dual role as assessor and feedback provider (Kumar & Stracke, 2011). In addition, the practice of peer assessment and feedback may address inconsistency issues in the gap between self-evaluation and the instructor’s/ examiner’s evaluation. Research has shown positive impacts of peer feedback on the improvement of assessment literacy, including the understanding of marking criteria and assessment purpose, the ability to benchmark work quality and research standards, an awareness of thesis/dissertation genre, improvement in academic writing skills, and the enhancement of audience awareness (Dickson et al., 2019; Yu, 2019; Man et al., 2018). In addition, peer feedback engages students in academic conversation that not only contributes to the establishment of a learning community and sense of belonging (Man et al., 2018), but also reduces anxiety among learners by opening up an opportunity to clarify the understanding of course work and seek support (Dickson et al., 2019).

Recommendation 3: Enhancing feedback practice with learning technology

As shown in the data, time constraints are one of the key issues that hamper the usefulness of feedback. This is especially a challenge in contexts with large and diverse student cohorts. Recent advancement of learning technology has shown promising results in addressing the lagged time in feedback provision. For example, learning analytics explores methods capable of collecting and analysing real-time data that learners produce during learning activities, and feeds the analysis results back to teachers or/and students. In blended-learning scenarios, the immediacy of feedback produced by learning analytics allows teachers to adjust teaching prior or during the course to tackle areas that students seem to struggle with (Shimada & Konomi, 2017). Learning analytics can also leverage the efforts in feedback provision by personalising feedback at scale (Gasevic et al., 2019; Pardo et al., 2019). As learning analytics facilitates a continuous feedback loop from learner to data, metrics, and interventions (Clow, 2012), it also allows both teachers and students to assess the impact of feedback on learning strategies and outcomes, thereby making further adjustments on knowledge, beliefs, goals, strategies, and tactics (Butler & Winne, 1995).

References

Butler, D. L., & Winne, P. H. (1995). Feedback and self-regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of educational research, 65(3), 245–281.

Clow, D. (2012). The learning analytics cycle: Closing the loop effectively. In Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on learning analytics and knowledge (pp. 134–138). ACM.

Dickson, H., Harvey, J., & Blackwood, N. (2019). Feedback, feedforward: evaluating the effectiveness of an oral peer review exercise amongst postgraduate students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(5), 692–704.

Dunworth, K., & Sanchez, H. S. (2016). Perceptions of quality in staff-student written feedback in higher education: a case study. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(5), 576–589.

Gasevic, D., Tsai, Y.-S., Dawson, S., & Pardo, A. (2019). How do we start? an approach to learning analytics adoption in higher education. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology.

Kumar, V., & Stracke, E. (2011). Examiners’ reports on theses: Feedback or assessment? Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(4), 211–222.

Man, D., Xu, Y., & O’Toole, J. M. (2018). Understanding autonomous peer feedback practices among post- graduate students: a case study in a chinese university. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(4), 527–536.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in higher education, 31(2), 199–218.

Pardo, A., Jovanovic, J., Dawson, S., Gaˇsevi ́c, D., & Mirriahi, N. (2019). Using learning analytics to scale the provision of personalised feedback. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 128–138.

Shimada, A., & Konomi, S. (2017). A lecture supporting system based on real-time learning analytics. International Association for Development of the Information Society.

Yu, S. (2019). Learning from giving peer feedback on postgraduate theses: Voices from master’s students in the macau efl context. Assessing Writing, 40, 42–52.